In financial markets, a distinction is often made between signal and noise when it comes to company information. How will financial market players perceive ESRS reports? As useful signals? Or as superfluous noise?

The reality of ESG use

Although countless academic studies on ESG have been published in recent years, the question of how exactly investors use this information remains largely unanswered. It is often assumed that investors read companies’ detailed reports – including ESG reports – in their entirety, despite significant shortcomings such as the lack of comparability and standardization in ESG data. The idea that annual reports are widely read is often fueled by investors themselves, for example when asked about their sources of information as part of academic research projects. This can be explained by a confirmation bias (“social desirability bias”). Financial market players themselves are often of the opinion that they should actually read annual reports. However, experience shows that financial market players only read sustainability reports occasionally and when they do, they do so selectively and in search of a specific detail.

Only very few investment professionals deal with sustainability reports. The vast majority probably have little idea what these reports and data look like and what benefits they can offer for decision-making.

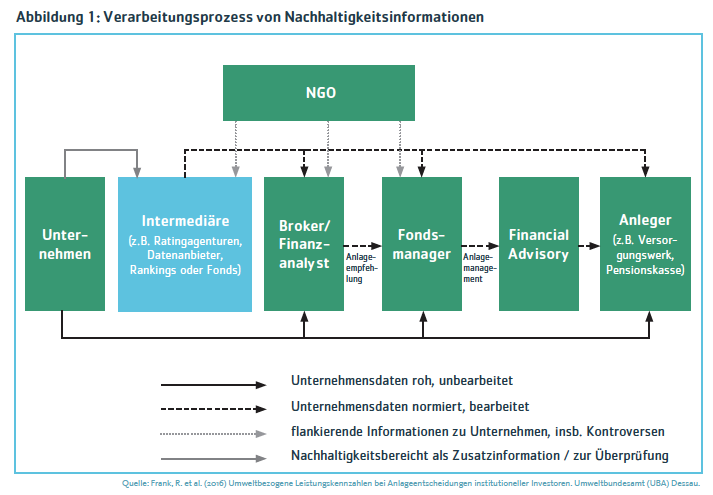

Evidence for this statement is provided by a research project carried out by DVFA together with Prof. Dr. Alexander Bassen from the University of Hamburg and PwC on behalf of the German Federal Environment Agency (UBA). The aim of the project was to investigate how ESG data is incorporated into the investment decisions of professional capital market players. The results of the study show that the majority of asset managers and sell-side houses purchase ESG data from ESG rating agencies and data providers and integrate it into their own databases as a “data feed”. Although this makes the ESG data available to investment professionals for parameterization (selection, weighting), it is generally no longer primary data, but secondary data that has been standardized and processed by ESG rating analysts.

Behavior and distortions

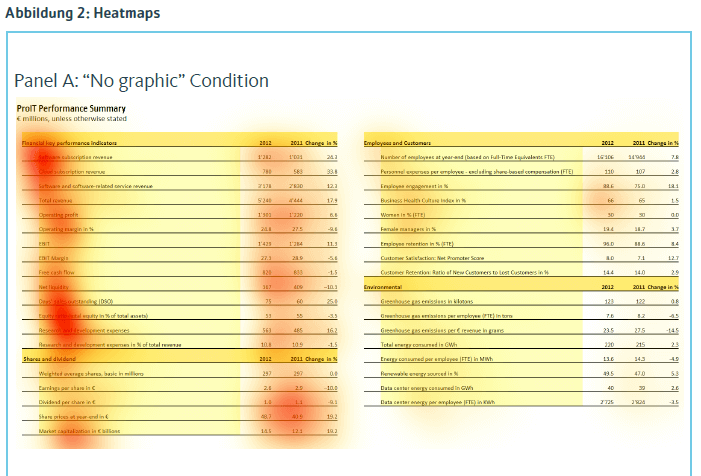

In order to better understand the actual use of ESG data by financial market players, Prof. Dr. Markus Arnold from the University of Bern, Prof. Dr. Alexander Bassen from the University of Hamburg and the author of this article conducted several experiments. One of the methods we used was eye tracking, which allowed us to analyze exactly which information actually attracts attention when looking at company data. Our central question was whether the biases known from behavioral economics, i.e. distortions of decisions and judgments, also occur in connection with ESG. For the heat maps shown in Figure 2, the eye movements of test subjects are recorded while they are looking at company data. When a test participant’s gaze lingers on a certain spot, the eye tracking equipment generates a red “cloud”. The results were revealing: without a targeted focus of attention, the ESG data presented in the right-hand column was often overlooked compared to the financial data in the left-hand column (top image). However, when attention was drawn to ESG data through visual highlighting – such as an ESG graphic – ESG was perceived (bottom figure). From a rational economic perspective, investment professionals should take note of data because it is either relevant or useful for decision-making. Graphical “reinforcement” is neither necessary nor logical from this perspective.

Biases in dealing with ESG data

In another experiment, capital market players in a group of several participants were asked to rate the financial results (“baseline treatment”) or financial results and ESG data (“experimental treatment”) of a fictitious company on a scale of 0-100, and at the same time estimate what the average rating would be across all participants in the group. Initially, the participants kept their ratings to themselves until the experimenters had collected the results and calculated an average for the entire group. The participants were then told the average rating, so that each subject now knew three judgments: their own original judgment, their assessment of the market average, and the real judgment of the “market”. The participants were then given the opportunity to revise or maintain their original assessment.

The results show that uncertainty is growing among ESG: “am I right in my judgment and everyone else doesn’t understand ESG as well as I do?” or “do the others see something in the data that I’m missing?” -. An anchoring bias can be observed when investment professionals revise their initial judgments, especially if there is a significant deviation between their own initial judgments and the market average. At the same time, overconfidence occurs, which is exacerbated when ESG is added.

A brief interim conclusion

- ESG data is typically incorporated into investment decisions via ESG rating agencies and data providers and only very rarely by direct means (“reading”). As a result, investment professionals often lack experience in dealing with sustainability reports and data.

- A lack of knowledge increases uncertainty in dealing with ESG, which reinforces existing behavioral biases.

- ESRS-based data is way more precise than ESG data, is verified, and is based on scientific definitions.

- However, the high granularity of ESRS and the large number of data points are overkill for most investment analysis applications.

- The materiality analysis does not differentiate between strategic topics and hygiene factors.

The dilemma

On the one hand, it is foreseeable that we will soon see an unprecedented number of companies with ESRS reports – and not just in the European Union – including those that were previously exempt from any mandatory sustainability reporting. The ESRS will create a universe of largely standardized ESG reports across numerous industries.

On the other hand, the interest of investors and financial analysts in ESG seems to be low so far. ESG data that does reach investors comes predominantly from sources such as ESG rating agencies. Even when ESG data is available, it is rarely used – either because it is considered unimportant or because other market participants do not use it either.

So where does the confidence come from that ESRS reports can actually influence the investment decisions of professional investors and analysts or lenders?

The transformation through ESRS

The question goes in the wrong direction. It is better to focus on how the application of ESRS changes the companies themselves and contributes to their transformation. Two central aspects are at the forefront here:

- Strategic positioning through materiality analysis

- Integration of sustainability into central corporate processes such as strategy and risk management

The analysis of double materiality requires companies to set up a systematic process. This process is based on the involvement of stakeholders and includes the quantification of:

- Impacts: How does the company influence the environment and society?

- Effects: How do developments in the environment and society affect the company financially?

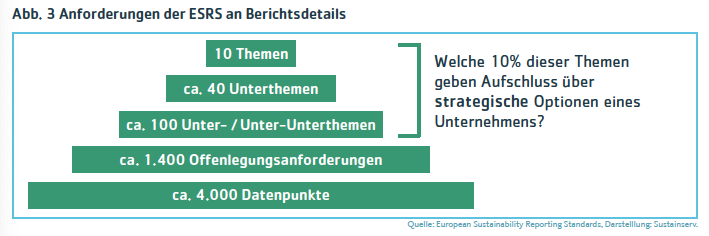

The key is to identify and utilize the truly strategic 10% of these 96 topics.

In addition, risks and opportunities as well as probabilities of occurrence are identified and documented in order to withstand an external audit. The basis for the review of potentially material topics is a comprehensive catalog of 96 topics, sub-topics and sub-sub-topics, which are linked to a large number of data points. However, not all data points are equally relevant to the strategic direction and may be considered “noise”.

By focusing on 3-5 key topics, companies can sharpen their strategic positioning and tell their story more convincingly to the capital market. At the same time, investors and lenders can use these central themes (“signals”) to make more informed valuations.

Mainstreaming ESG within the company

The ESRS are structured by four content anchors:

- Governance

- Strategy

- Risk management

- Key figures and targets

ESRS have this structure in common with the TCFD framework (“Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures”). These content anchors raise a question between the lines: How can we tell that a company is actually living sustainability and not just superficially engaging in “ESG acrobatics” or greenwashing?

This can be recognized by the fact that:

- senior management communicates actively and competently on sustainability issues instead of delegating responsibility to a staff unit;

- sustainability is firmly anchored in the corporate strategy and the strategy department is actively involved;

- ESG-related risks, such as physical or transitory risks, are an integral part of risk management; and

- opportunities and risks are regularly measured and integrated into corporate planning.

Companies are required to reorganize and reposition themselves in order to meet the requirements of the ESRS. Departments that previously operated in isolation, such as Risk Management, EHS, HR, Purchasing and Legal, must now work together across functions. The sustainability department is stepping out of its previous isolated position and taking on a moderating role within the company.

Conclusion

- ESRS transform corporate processes and the way sustainability issues are dealt with – this makes companies more resilient and serves economic, ecological and ethical sustainability.

- The granularity and depth of detail of the ESRS reports enable companies to provide complete and plausible evidence of their business activities. This is an effective tool against greenwashing!

This article was published as a supplement in the Fall 2024 issue of The Reporting Times by the Center for Corporate Reporting. The PDF can be read here (only in German).

Get in touch. We are happy to tell you more about it.